Mary Magdalene You Must Be Born Again

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/mary-magdalene-penitent-Pedro-de-Moya631.jpg)

The whole history of western civilization is epitomized in the cult of Mary Magdalene. For many centuries the most obsessively revered of saints, this woman became the embodiment of Christian devotion, which was defined as repentance. Still she was but elusively identified in Scripture, and has thus served equally a scrim onto which a succession of fantasies has been projected. In 1 age after another her image was reinvented, from prostitute to sibyl to mystic to chaste nun to passive helpmeet to feminist icon to the dame of divinity's secret dynasty. How the past is remembered, how sexual want is domesticated, how men and women negotiate their split impulses; how power inevitably seeks sanctification, how tradition becomes authoritative, how revolutions are co-opted; how fallibility is reckoned with, and how sweet devotion tin be made to serve violent domination—all these cultural questions helped shape the story of the woman who befriended Jesus of Nazareth.

Who was she? From the New Attestation, one can conclude that Mary of Magdala (her hometown, a village on the shore of the Body of water of Galilee) was a leading effigy amongst those attracted to Jesus. When the men in that visitor abased him at the hour of mortal danger, Mary of Magdala was i of the women who stayed with him, fifty-fifty to the Crucifixion. She was nowadays at the tomb, the get-go person to whom Jesus appeared after his resurrection and the beginning to preach the "Practiced News" of that miracle. These are among the few specific assertions made almost Mary Magdalene in the Gospels. From other texts of the early Christian era, information technology seems that her status as an "apostle," in the years after Jesus' expiry, rivaled even that of Peter. This prominence derived from the intimacy of her relationship with Jesus, which, according to some accounts, had a physical aspect that included kissing. Get-go with the threads of these few statements in the earliest Christian records, dating to the first through third centuries, an elaborate tapestry was woven, leading to a portrait of St. Mary Magdalene in which the most consequential note—that she was a repentant prostitute—is almost certainly untrue. On that simulated notation hangs the dual use to which her legend has been put always since: discrediting sexuality in general and disempowering women in particular.

Confusions fastened to Mary Magdalene's character were compounded across time as her prototype was conscripted into 1 power struggle later some other, and twisted accordingly. In conflicts that divers the Christian Church—over attitudes toward the cloth world, focused on sexuality; the dominance of an all-male clergy; the coming of celibacy; the branding of theological diverseness as heresy; the sublimations of courtly love; the unleashing of "chivalrous" violence; the marketing of sainthood, whether in the fourth dimension of Constantine, the Counter-Reformation, the Romantic era, or the Industrial Age—through all of these, reinventions of Mary Magdalene played their role. Her contempo reemergence in a novel and film as the hole-and-corner wife of Jesus and the female parent of his fate-burdened girl shows that the conscripting and twisting are withal going on.

Merely, in truth, the defoliation starts with the Gospels themselves.

In the gospels several women come into the story of Jesus with neat energy, including erotic free energy. There are several Marys—not least, of course, Mary the mother of Jesus. But at that place is Mary of Bethany, sister of Martha and Lazarus. In that location is Mary the mother of James and Joseph, and Mary the married woman of Clopas. Equally important, in that location are three unnamed women who are expressly identified as sexual sinners—the woman with a "bad name" who wipes Jesus' feet with ointment every bit a signal of repentance, a Samaritan woman whom Jesus meets at a well and an adulteress whom Pharisees haul before Jesus to see if he will condemn her. The first affair to practice in unraveling the tapestry of Mary Magdalene is to tease out the threads that properly belong to these other women. Some of these threads are themselves quite knotted.

Information technology will help to remember how the story that includes them all came to be written. The four Gospels are not eyewitness accounts. They were written 35 to 65 years after Jesus' death, a jelling of divide oral traditions that had taken form in dispersed Christian communities. Jesus died in about the yr a.d. 30. The Gospels of Mark, Matthew and Luke engagement to nigh 65 to 85, and have sources and themes in common. The Gospel of John was equanimous around ninety to 95 and is singled-out. So when we read about Mary Magdalene in each of the Gospels, as when we read nigh Jesus, what we are getting is non history only retentivity—retentivity shaped by time, past shades of emphasis and by efforts to make distinctive theological points. And already, even in that early menses—as is evident when the varied accounts are measured against each other—the memory is blurred.

Regarding Mary of Magdala, the confusion begins in the eighth chapter of Luke:

Now later on this [Jesus] made his way through towns and villages preaching, and proclaiming the Good News of the kingdom of God. With him went the Twelve, as well as certain women who had been cured of evil spirits and ailments: Mary surnamed the Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out, Joanna the married woman of Herod'southward steward Chuza, Susanna, and several others who provided for them out of their own resource.

Two things of note are implied in this passage. First, these women "provided for" Jesus and the Twelve, which suggests that the women were well-to-practice, respectable figures. (It is possible this was an attribution, to Jesus' fourth dimension, of a office prosperous women played some years later.) Second, they all had been cured of something, including Mary Magdalene. The "7 demons," as applied to her, indicates an disquiet (not necessarily possession) of a certain severity. Soon enough, as the blurring piece of work of memory continued, so equally the written Gospel was read by Gentiles unfamiliar with such coded language, those "demons" would be taken as a sign of a moral infirmity.

This otherwise innocuous reference to Mary Magdalene takes on a kind of radioactive narrative energy because of what immediately precedes it at the end of the seventh chapter, an anecdote of stupendous power:

One of the Pharisees invited [Jesus] to a repast. When he arrived at the Pharisee'south house and took his place at tabular array, a woman came in, who had a bad name in the town. She had heard he was dining with the Pharisee and had brought with her an alabaster jar of ointment. She waited behind him at his feet, weeping, and her tears fell on his feet, and she wiped them away with her hair; then she covered his feet with kisses and all-powerful them with the ointment.

When the Pharisee who had invited him saw this, he said to himself, "If this human being were a prophet, he would know who this woman is that is touching him and what a bad name she has."

But Jesus refuses to condemn her, or even to deflect her gesture. Indeed, he recognizes it as a sign that "her many sins must accept been forgiven her, or she would not have shown such cracking love." "Your faith has saved you," Jesus tells her. "Go in peace."

This story of the adult female with the bad name, the alabaster jar, the loose pilus, the "many sins," the stricken conscience, the ointment, the rubbing of feet and the kissing would, over fourth dimension, get the dramatic high point of the story of Mary Magdalene. The scene would be explicitly attached to her, and rendered again and again by the greatest Christian artists. Only even a casual reading of this text, still charged its juxtaposition with the subsequent verses, suggests that the two women have zero to exercise with each other—that the weeping anointer is no more connected to Mary of Magdala than she is to Joanna or Susanna.

Other verses in other Gospels only add to the complication. Matthew gives an account of the same incident, for example, but to make a different point and with a crucial detail added:

Jesus was at Bethany in the firm of Simon the leper, when a woman came to him with an alabaster jar of the most expensive ointment, and poured it on his caput as he was at table. When they saw this, the disciples were indignant. "Why this waste material?" they said. "This could take been sold at a loftier price and the coin given to the poor." Jesus noticed this. "Why are you upsetting the woman?" he said to them.... "When she poured this ointment on my body, she did it to prepare me for burying. I tell y'all solemnly, wherever in all the globe this Good News is proclaimed, what she has done will be told too, in remembrance of her."

This passage shows what Scripture scholars ordinarily call the "telephone game" character of the oral tradition from which the Gospels grew. Instead of Luke'south Pharisee, whose name is Simon, we find in Matthew "Simon the leper." Nearly tellingly, this anointing is specifically referred to as the traditional rubbing of a corpse with oil, so the human activity is an explicit foreshadowing of Jesus' death. In Matthew, and in Marking, the story of the unnamed adult female puts her acceptance of Jesus' coming decease in glorious contrast to the (male) disciples' refusal to take Jesus' predictions of his decease seriously. Merely in other passages, Mary Magdalene is associated past name with the burial of Jesus, which helps explain why information technology was easy to confuse this anonymous woman with her.

Indeed, with this incident both Matthew's and Mark's narratives begin the motion toward the climax of the Crucifixion, because i of the disciples—"the homo called Judas"—goes, in the very side by side verse, to the primary priests to beguile Jesus.

In the passages well-nigh the anointings, the woman is identified by the "alabaster jar," but in Luke, with no reference to the death ritual, there are articulate erotic overtones; a man of that fourth dimension was to see a adult female's loosened hair merely in the intimacy of the bedroom. The offense taken past witnesses in Luke concerns sex, while in Matthew and Mark it concerns coin. And, in Luke, the adult female's tears, together with Jesus' words, define the encounter as one of abject repentance.

But the complications mountain. Matthew and Mark say the anointing incident occurred at Bethany, a detail that echoes in the Gospel of John, which has yet another Mary, the sis of Martha and Lazarus, and withal another anointing story:

Half dozen days earlier the Passover, Jesus went to Bethany, where Lazarus was, whom he had raised from the dead. They gave a dinner for him there; Martha waited on them and Lazarus was amid those at table. Mary brought in a pound of very costly ointment, pure nard, and with information technology anointed the feet of Jesus, wiping them with her hair.

Judas objects in the name of the poor, and one time more Jesus is shown defending the woman. "Go out her lonely; she had to go on this odor for the mean solar day of my burial," he says. "You have the poor with yous e'er, you lot will non always have me."

Every bit before, the anointing foreshadows the Crucifixion. There is besides resentment at the waste of a luxury proficient, so death and money ascertain the content of the run into. But the loose hair implies the erotic as well.

The death of Jesus on Golgotha, where Mary Magdalene is expressly identified as one of the women who refused to leave him, leads to what is by far the nearly of import affirmation about her. All four Gospels (and another early Christian text, the Gospel of Peter) explicitly proper name her as present at the tomb, and in John she is the starting time witness to the resurrection of Jesus. This—not repentance, not sexual renunciation—is her greatest claim. Unlike the men who scattered and ran, who lost organized religion, who betrayed Jesus, the women stayed. (Even while Christian memory glorifies this act of loyalty, its historical context may have been less noble: the men in Jesus' company were far more likely to have been arrested than the women.) And chief amid them was Mary Magdalene. The Gospel of John puts the story poignantly:

Information technology was very early on the get-go day of the week and still nighttime, when Mary of Magdala came to the tomb. She saw that the rock had been moved away from the tomb and came running to Simon Peter and the other disciple, the one Jesus loved. "They have taken the Lord out of the tomb," she said, "and nosotros don't know where they have put him."

Peter and the others rush to the tomb to come across for themselves, and then disperse again.

Meanwhile Mary stayed outside almost the tomb, weeping. Then, still weeping, she stooped to expect inside, and saw ii angels in white sitting where the body of Jesus had been, one at the head, the other at the anxiety. They said, "Adult female, why are you weeping?" "They have taken my Lord abroad," she replied, "and I don't know where they have put him." As she said this she turned around and saw Jesus continuing in that location, though she did not recognize him. Jesus said, "Woman, why are you lot weeping? Who are you looking for?" Supposing him to exist the gardener, she said, "Sir, if you lot have taken him away, tell me where you have put him, and I will become and remove him." Jesus said, "Mary!" She knew him then and said to him in Hebrew, "Rabbuni!"—which means Master. Jesus said to her, "Practice not cling to me, considering I have not yet ascended to...my Father and your Father, to my God and your God." So Mary of Magdala went and told the disciples that she had seen the Lord and that he had said these things to her.

As the story of Jesus was told and told again in those first decades, narrative adjustments in issue and character were inevitable, and confusion of ane with the other was a mark of the style the Gospels were handed on. Near Christians were illiterate; they received their traditions through a complex piece of work of memory and interpretation, not history, that led only eventually to texts. One time the sacred texts were authoritatively fix, the exegetes who interpreted them could brand careful distinctions, keeping the roster of women split, but common preachers were less careful. The telling of anecdotes was essential to them, and then alterations were certain to occur.

The multiplicity of the Marys past itself was enough to mix things upwardly—as were the various accounts of anointing, which in one place is the deed of a loose-haired prostitute, in another of a modest stranger preparing Jesus for the tomb, and in yet another of a beloved friend named Mary. Women who weep, albeit in a range of circumstances, emerged as a motif. As with every narrative, erotic details loomed big, especially because Jesus' attitude toward women with sexual histories was i of the things that set him apart from other teachers of the time. Not only was Jesus remembered as treating women with respect, equally equals in his circumvolve; not only did he refuse to reduce them to their sexuality; Jesus was expressly portrayed equally a human being who loved women, and whom women loved.

The climax of that theme takes place in the garden of the tomb, with that one discussion of address, "Mary!" Information technology was enough to make her recognize him, and her response is clear from what he says so: "Do not cling to me." Whatever it was before, bodily expression between Jesus and Mary of Magdala must be different now.

Out of these disparate threads—the various female figures, the ointment, the pilus, the weeping, the unparalleled intimacy at the tomb—a new graphic symbol was created for Mary Magdalene. Out of the threads, that is, a tapestry was woven—a single narrative line. Across time, this Mary went from being an important disciple whose superior condition depended on the conviction Jesus himself had invested in her, to a repentant whore whose condition depended on the erotic charge of her history and the misery of her stricken conscience. In part, this evolution arose out of a natural impulse to see the fragments of Scripture whole, to make a disjointed narrative adhere, with dissever choices and consequences being tied to each other in one drama. It is as if Aristotle's principle of unity, given in Poetics, was imposed later on the fact on the foundational texts of Christianity.

Thus, for example, out of detached episodes in the Gospel narratives, some readers would even create a far more unified—more satisfying—legend according to which Mary of Magdala was the unnamed woman beingness married at the wedding banquet of Cana, where Jesus famously turned water into wine. Her spouse, in this telling, was John, whom Jesus immediately recruited to be one of the Twelve. When John went off from Cana with the Lord, leaving his new wife behind, she collapsed in a fit of loneliness and jealousy and began to sell herself to other men. She next appeared in the narrative as the past and then notorious adulteress whom the Pharisees thrust before Jesus. When Jesus refused to condemn her, she saw the error of her ways. Consequently, she went and got her precious ointment and spread it on his feet, weeping in sorrow. From then on she followed him, in chastity and devotion, her love forever unconsummated—"Exercise not cling to me!"—and more intense for being and so.

Such a woman lives on as Mary Magdalene in Western Christianity and in the secular Western imagination, right down, say, to the rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar, in which Mary Magdalene sings, "I don't know how to love him...He'south only a man, and I've had so many men before...I want him so. I dear him so." The story has timeless appeal, start, considering that problem of "how"—whether love should be eros or agape; sensual or spiritual; a matter of longing or consummation—defines the human condition. What makes the conflict universal is the dual experience of sex: the necessary means of reproduction and the madness of passionate encounter. For women, the maternal can seem to be at odds with the erotic, a tension that in men can be reduced to the well-known reverse fantasies of the madonna and the whore. I write equally a man, yet it seems to me in women this tension is expressed in attitudes not toward men, but toward femaleness itself. The paradigm of Mary Magdalene gives expression to such tensions, and draws power from them, especially when it is twinned to the image of that other Mary, Jesus' mother.

Christians may worship the Blest Virgin, but it is Magdalene with whom they identify. What makes her compelling is that she is not merely the whore in dissimilarity to the Madonna who is the mother of Jesus, but that she combines both figures in herself. Pure by virtue of her repentance, she nevertheless remains a woman with a past. Her conversion, instead of removing her erotic attraction, heightens it. The misery of self-allegation, known in one way or another to every homo beingness, finds release in a figure whose apple-polishing penitence is the condition of recovery. That she is sorry for having led the willful life of a sex object makes her only more compelling every bit what might be called a repentance object.

So the invention of the character of Mary Magdalene every bit repentant prostitute can be seen as having come about because of pressures inhering in the narrative course and in the primordial urge to requite expression to the inevitable tensions of sexual restlessness. But neither of these was the chief factor in the conversion of Mary Magdalene'due south image, from one that challenged men'due south misogynist assumptions to ane that confirmed them. The principal factor in that transformation was, in fact, the manipulation of her image by those very men. The mutation took a long fourth dimension to accomplish—fully the starting time 600 years of the Christian era.

Once more, it helps to have a chronology in mind, with a focus on the place of women in the Jesus movement. Phase i is the time of Jesus himself, and there is every reason to believe that, co-ordinate to his teaching and in his circle, women were uniquely empowered as fully equal. In phase two, when the norms and assumptions of the Jesus community were beingness written downwards, the equality of women is reflected in the messages of St. Paul (c. 50-threescore), who names women as full partners—his partners—in the Christian motility, and in the Gospel accounts that requite evidence of Jesus' own attitudes and highlight women whose courage and fidelity stand up in marked contrast to the men's cowardice.

Merely past phase three—after the Gospels are written, but earlier the New Testament is defined as such—Jesus' rejection of the prevailing male potency was being eroded in the Christian community. The Gospels themselves, written in those several decades afterwards Jesus, can be read to suggest this erosion considering of their emphasis on the authorisation of "the Twelve," who are all males. (The all-male composition of "the Twelve" is expressly used past the Vatican today to exclude women from ordination.) Only in the books of the New Testament, the argument among Christians over the place of women in the community is implicit; it becomes quite explicit in other sacred texts of that early flow. Not surprisingly, possibly, the effigy who most embodies the imaginative and theological disharmonize over the identify of women in the "church," every bit it had begun to telephone call itself, is Mary Magdalene.

Here, it is useful to recall not but how the New Testament texts were equanimous, but as well how they were selected as a sacred literature. The popular assumption is that the Epistles of Paul and James and the four Gospels, together with the Acts of the Apostles and the Volume of Revelation, were pretty much what the early Christian community had past way of foundational writings. These texts, believed to be "inspired by the Holy Spirit," are regarded as having somehow been conveyed past God to the church, and joined to the previously "inspired" and selected books of the Old Testament to form "the Bible." Merely the holy books of Christianity (like the holy books of Judaism, for that matter) were established past a procedure far more complicated (and human) than that.

The explosive spread of the Skillful News of Jesus around the Mediterranean world meant that distinct Christian communities were springing up all over the place. There was a lively diversity of belief and practice, which was reflected in the oral traditions and, later, texts those communities drew on. In other words, there were many other texts that could have been included in the "catechism" (or listing), but weren't.

It was not until the fourth century that the list of canonized books nosotros now know as the New Testament was established. This amounted to a milestone on the road toward the church'due south definition of itself precisely in opposition to Judaism. At the same time, and more subtly, the church was on the manner toward understanding itself in opposition to women. Once the church began to enforce the "orthodoxy" of what information technology deemed Scripture and its doctrinally defined creed, rejected texts—and sometimes the people who prized them, too known every bit heretics—were destroyed. This was a matter partly of theological dispute—If Jesus was divine, in what fashion?—and partly of boundary-drawing against Judaism. Just there was also an expressly philosophical inquiry at work, as Christians, similar their pagan contemporaries, sought to ascertain the relationship between spirit and thing. Among Christians, that argument would shortly enough focus on sexuality—and its battleground would be the existential tension between male and female.

As the sacred books were canonized, which texts were excluded, and why? This is the long way around, only nosotros are back to our subject, because one of the most important Christian texts to be found exterior the New Testament canon is the and so-called Gospel of Mary, a telling of the Jesus-move story that features Mary Magdalene (decidedly non the woman of the "alabaster jar") as ane of its most powerful leaders. Only as the "canonical" Gospels emerged from communities that associated themselves with the "evangelists," who may not actually have "written" the texts, this one is named for Mary non considering she "wrote" it, but because it emerged from a customs that recognized her authority.

Whether through suppression or neglect, the Gospel of Mary was lost in the early on menstruation—merely every bit the real Mary Magdalene was beginning to disappear into the writhing misery of a penitent whore, and as women were disappearing from the church's inner circumvolve. Information technology reappeared in 1896, when a well-preserved, if incomplete, fifth-century copy of a certificate dating to the second century showed up for auction in Cairo; eventually, other fragments of this text were found. Only slowly through the 20th century did scholars appreciate what the rediscovered Gospel revealed, a process that culminated with the publication in 2003 of The Gospel of Mary of Magdala: Jesus and the Starting time Woman Apostle by Karen 50. King.

Although Jesus rejected male person say-so, equally symbolized in his commissioning of Mary Magdalene to spread word of the Resurrection, male dominance gradually made a powerful comeback inside the Jesus movement. But for that to happen, the commissioning of Mary Magdalene had to be reinvented. One sees that very thing nether way in the Gospel of Mary.

For example, Peter'southward preeminence is elsewhere taken for granted (in Matthew, Jesus says, "You are Peter and on this rock I will build my Church"). Here, he defers to her:

Peter said to Mary, "Sister, nosotros know that the Savior loved you more than than all other women. Tell us the words of the Savior that yous recall, the things which you know that we don't because we haven't heard them."

Mary responded, "I will teach you well-nigh what is hidden from you." And she began to speak these words to them.

Mary recalls her vision, a kind of esoteric description of the ascent of the soul. The disciples Peter and Andrew are disturbed—not by what she says, just past how she knows it. And now a jealous Peter complains to his fellows, "Did [Jesus] choose her over united states of america?" This draws a precipitous rebuke from some other apostle, Levi, who says, "If the Savior made her worthy, who are you and so for your part to reject her?"

That was the question non only about Mary Magdalene, but about women by and large. It should be no surprise, given how successfully the excluding dominance of males established itself in the church of the "Fathers," that the Gospel of Mary was i of the texts shunted aside in the quaternary century. As that text shows, the early prototype of this Mary equally a trusted apostle of Jesus, reflected fifty-fifty in the approved Gospel texts, proved to exist a major obstacle to establishing that male person dominance, which is why, whatever other "heretical" problems this gospel posed, that epitome had to exist recast as ane of subservience.

Simultaneously, the emphasis on sexuality as the root of all evil served to subordinate all women. The aboriginal Roman globe was rife with flesh-antisocial spiritualities—Stoicism, Manichaeism, Neoplatonism—and they influenced Christian thinking just as information technology was jelling into "doctrine." Thus the need to disempower the figure of Mary Magdalene, and then that her succeeding sisters in the church would not compete with men for power, meshed with the impulse to discredit women more often than not. This was about efficiently done by reducing them to their sexuality, even as sexuality itself was reduced to the realm of temptation, the source of human being unworthiness. All of this—from the sexualizing of Mary Magdalene, to the emphatic veneration of the virginity of Mary, the mother of Jesus, to the embrace of celibacy every bit a clerical ideal, to the marginalizing of female devotion, to the recasting of piety equally self-denial, particularly through penitential cults—came to a kind of defining climax at the end of the sixth century. Information technology was then that all the philosophical, theological and ecclesiastical impulses curved back to Scripture, seeking an ultimate imprimatur for what by then was a firm cultural prejudice. It was then that the rails along which the church—and the Western imagination—would run were ready.

Pope Gregory I (c. 540-604) was born an aristocrat and served as the prefect of the metropolis of Rome. After his father's death, he gave everything away and turned his deluxe Roman home into a monastery, where he became a lowly monk. It was a time of plague, and indeed the previous pope, Pelagius 2, had died of it. When the saintly Gregory was elected to succeed him, he at one time emphasized penitential forms of worship every bit a manner of warding off the disease. His pontificate marked a solidifying of discipline and thought, a fourth dimension of reform and invention both. But it all occurred against the backdrop of the plague, a doom-laden circumstance in which the abjectly repentant Mary Magdalene, warding off the spiritual plague of damnation, could come up into her own. With Gregory's help, she did.

Known as Gregory the Great, he remains one of the near influential figures ever to serve as pope, and in a famous series of sermons on Mary Magdalene, given in Rome in about the yr 591, he put the seal on what until and then had been a mutual just unsanctioned reading of her story. With that, Mary's conflicted image was, in the words of Susan Haskins, author of Mary Magdalene: Myth and Metaphor, "finally settled...for almost fourteen hundred years."

It all went back to those Gospel texts. Cutting through the exegetes' conscientious distinctions—the various Marys, the sinful women—that had fabricated a bald combining of the figures hard to sustain, Gregory, standing on his own potency, offered his decoding of the relevant Gospel texts. He established the context within which their meaning was measured from then on:

She whom Luke calls the sinful adult female, whom John calls Mary, nosotros believe to be the Mary from whom seven devils were ejected co-ordinate to Mark. And what did these seven devils signify, if not all the vices?

There information technology was—the adult female of the "alabaster jar" named by the pope himself equally Mary of Magdala. He defined her:

It is articulate, brothers, that the woman previously used the unguent to perfume her mankind in forbidden acts. What she therefore displayed more scandalously, she was now offering to God in a more than praiseworthy manner. She had coveted with earthly eyes, but at present through penitence these are consumed with tears. She displayed her hair to gear up off her face, but now her pilus dries her tears. She had spoken proud things with her mouth, merely in kissing the Lord's feet, she now planted her oral cavity on the Redeemer'south feet. For every delight, therefore, she had had in herself, she now immolated herself. She turned the mass of her crimes to virtues, in order to serve God entirely in penance.

The address "brothers" is the inkling. Through the Middle Ages and the Counter-Reformation, into the modernistic menses and against the Enlightenment, monks and priests would read Gregory'due south words, and through them they would read the Gospels' texts themselves. Chivalrous knights, nuns establishing houses for unwed mothers, courtly lovers, desperate sinners, frustrated celibates and an endless succession of preachers would treat Gregory's reading as literally the gospel truth. Holy Writ, having recast what had actually taken identify in the lifetime of Jesus, was itself recast.

The men of the church building who benefited from the recasting, forever spared the presence of females in their sanctuaries, would not know that this was what had happened. Having created a myth, they would not call up that information technology was mythical. Their Mary Magdalene—no fiction, no composite, no expose of a once venerated adult female—became the only Mary Magdalene that had ever existed.

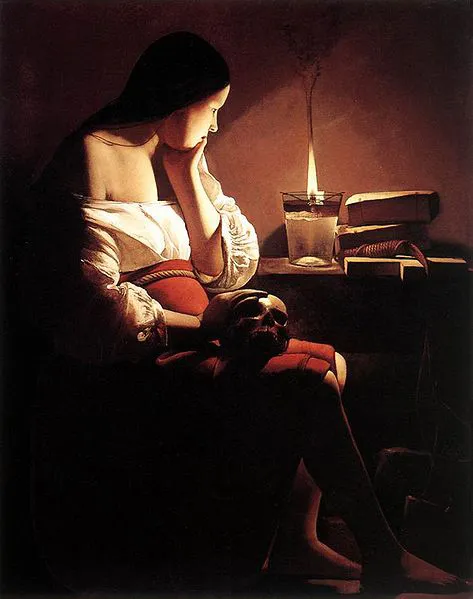

This obliteration of the textual distinctions served to evoke an platonic of virtue that drew its rut from being a celibate's vision, conjured for celibates. Gregory the Great'south overly particular involvement in the fallen woman's past—what that oil had been used for, how that hair had been displayed, that oral cavity—brought into the center of church piety a vaguely prurient energy that would thrive under the licensing sponsorship of one of the church building'due south most revered reforming popes. Somewhen, Magdalene, as a denuded object of Renaissance and Baroque painterly preoccupation, became a figure of nada less than holy pornography, guaranteeing the ever-lustful harlot—if lustful now for the ecstasy of holiness—a permanent place in the Catholic imagination.

Thus Mary of Magdala, who began as a powerful adult female at Jesus' side, "became," in Haskins' summary, "the redeemed whore and Christianity's model of repentance, a manageable, controllable figure, and effective weapon and musical instrument of propaganda against her own sex." In that location were reasons of narrative class for which this happened. There was a harnessing of sexual restlessness to this image. In that location was the humane entreatment of a story that emphasized the possibility of forgiveness and redemption. Merely what most drove the anti-sexual sexualizing of Mary Magdalene was the male demand to dominate women. In the Catholic Church, every bit elsewhere, that need is still existence met.

Mary Magdalene You Must Be Born Again

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/who-was-mary-magdalene-119565482/

0 Response to "Mary Magdalene You Must Be Born Again"

Post a Comment